Tanker rates are falling dramatically as the coronavirus-led drop off in demand outweighs the oil price war. Elsewhere, crew change restrictions are slowly being lifted in China, but national lockdowns are causing concern for seafarers in other parts of the world. As regards the containers sector, the outlook is becoming increasingly pessimistic

IN THIS new weekly briefing covering the coronavirus outbreak and its impact on shipping, the Lloyd’s List analyst team offer valuable insight, commentary and analysis on a sector-by-sector basis. Follow the links within the text to the relevant news items within each segment.

On Thursday March 26, reporters and analysts from across the Lloyd’s List and Lloyd’s List Intelligence team will host a webinar and live Q&A on the coronavirus effects on shipping. More details and information on how to register are available here.

You can also stay up to date with our special coronavirus home page, featuring daily updates and news from Lloyd’s List and our colleagues at sister title Insurance Day.

Tanker markets

Tanker rates are as much as 161% below record-breaking levels set a week ago as the dramatic, coronavirus-led collapse in crude demand overshadows the oil price war that sparked the earnings rally.

Oil trader Vitol’s chief executive Russel Hardy estimated the scale of the collapse peaking at between 15m-20m barrels per day during the next few weeks, averaging out to 5m bpd for 2020.

The world’s crude tanker fleet, comprising some 2,200 vessels, transports about half of the total 100m bpd of oil consumed, with Vitol one of the biggest shippers of both oil and refined products.

Very large crude carrier rates are now equivalent to earnings of $89,277 daily, according to the London-based Baltic Exchange, down from the record of $264,072 set on March 16. Suezmaxes are 161% lower at $50,512 per day, while aframax sizes declined for a second day, reaching $49,861.

“There’s a lot of oil in the market and there are a lot of stocks we’re going to have to build because oil isn’t going to be consumed,” Mr Hardy told Bloomberg TV on Wednesday in a rare interview. “Product inventories are building in north America, the US, Europe and India and refineries are going to have to cut runs.”

Global runs are already down by 7m bpd, he estimated, and further reductions needed. Crude storage is going to “fill up pretty quickly” he added, with a greater shortage of land-based facilities for refined products.

This will add to demand for floating storage, forecast to sharply rise in coming weeks. Crude and middle distillates stored on ships at anchor offshore is set to exceed current volumes last seen when the oil price fell in 2015. Crude in floating storage is already tracked as the most in at least 11 years, at just over 132m barrels, according to data from Lloyd’s List Intelligence.

Global land-based crude inventories in January, which include governments’ reserves, were 330m barrels below the record 2.9bn barrels reported in May 2016, Joint Organisations Data Initiative data show. January is the most recent month for which information is available. Vitol’s forecast of a 5m bpd contraction in demand implies a 1.82bn barrel oversupply unless oil companies begin production shut-ins.

The 20m barrels seen lost over the last month amounted to about 600m barrels for storage, Mr Hardy said, with some 300m to 400m barrels of shoreside capacity remaining. Once the wall is hit, producers will have to make a decision about whether or not they want to keep pushing oil in to the market, he added.

Chevron, Total and Shell all announced capex cuts this week, with scaling back of Permian shale production now expected to arrest growth of export markets for tankers shipping cargoes to Asia and Europe.

The rapidly changing demand picture comes as India, one of the biggest drivers of crude demand after China, went into lockdown for 21 days — further adding to demand destruction — while oil prices continued trading at 17-year lows.

This has also placed Saudi Arabia under scrutiny, after the kingdom pledged to flood the market with oil to retain market share, which first triggered the collapse in oil prices. Saudi shipping company Bahri chartered some 25 VLCCs on the spot market between March 9-20 to load extra cargoes, resulting in the rates spike seen in mid-March.

These VLCCs are now sailing to Saudi Arabia with loading dates starting from March 25 to April 2 (see map above). But with refineries worldwide cutting runs and the crude surplus rising, its unclear whether there will be buyers for cargoes to be loaded on the armada of VLCCs due to more people working from home and decisions taking longer.

At least four of the Bahri-chartered VLCCs are heading for the Red Sea port of Ain Sukhna where the national oil company has storage facilities, but a further 10 are sailing for the US Gulf, where refineries there are already reducing utilisation levels.

Crewing and regulatory issues

The outbreak of the coronavirus pandemic has prompted shipping companies to prohibit scheduled crew changes, governments to shut down borders and high-level regulatory meetings to be postponed.

Like the virus, the restriction of crew changes started with China and then crept into the other parts of the world. Similarly, as new cases of domestic infections are seemingly under control, the country is gradually relaxing the control measures for seafarers.

At a few ports, including Shanghai and Nanjing, crew replacement has been permitted on a case-by-case basis. The transport ministry also issued a policy guidance in a bid to expand the scale of the relief.

Beijing is targeting about 10,000 Chinese crew members whose service agreements or contracts will expire by the end of May and are due for shore leave.

Elsewhere, though, the situation is less optimistic. In the Philippines, one of the world’s largest seafarer nations, a complete ban on crew embarkment/disembarkment is still in force, with the country’s main island Luzon under an "enhanced community quarantine".

Indian seafarers are also being advised not to sign off from ships and return home after completing their contracts, except in an emergency, due to the country’s 21-day nationwide lockdown.

The crisis has forced shipping and seafaring organisations, such as the International Chamber of Shipping and the International Transport Workers Federation, as well as the European Community Shipowners Association and the European Transport Workers’ Federation, to work together to demand support and protection for seafarers and vessels from relevant institutions.

A key concern has been securing the exemption of seafarers from national travel bans that have been introduced, especially in Europe, to enable the continuation of trade and the smooth flow of supply chains.

They point out that 100,000 seafarers must change every month to comply with rules and regulations. The European Commission subsequently urged EU member states to exempt all transport workers from the coronavirus-related travel bans introduced.

Whether EU governments follow the advice, however, remains to be seen. After all, even the policy push from Beijing, which enjoys the supreme authority over its territory, faced resistance from local governments and port authorities regarding fears that the entry of crew members may compromise their hard work in tackling the public health crisis.

There are also financial issues in relation to who should bear the quarantine cost for seafarers. Should the government share the burden with shipowners and operators who have already suffered huge losses from the virus fallout?

Ecsa and the ETF have also asked the EU for financial assistance towards the shipping industry, with special measures to protect EU jobs, support for European banks lending to the shipping sector and flexible implementation of maritime state aid guidelines so that governments can freely help out those that will require it.

Meanwhile, with the International Maritime Organization headquarters shut down and meetings scheduled through May postponed, secretary-general Kitack Lim took to a video message urging pragmatism on crew changes, seafarer licenses and other regular fixtures in maritime regulation.

Containers

It was only a month ago that Maersk chief executive Søren Skou used the company’s annual report presentation to forecast a V-shaped recovery to the downturn caused by outbreak of coronavirus, which was at the time causing supply problems in China.

And it was only a week ago that the world’s largest container line had to suspend its earnings guidance for the year, as what once looked like a problem in an inland province in China became a global pandemic that has since rocked the global economy to its foundations.

While optimists like Rodolphe Saadé indicated that volumes would return to normal by the end of this month, others, such as Hapag-Lloyd’s Rolf Habben Jansen, have accepted that his company’s earnings outlook for 2020 is subject to considerably more uncertainty that usual.

When coronavirus was simply an issue in China, there were reasons to be optimistic. Constrained supply would lead to pent up demand that in turn would be reflected in higher volumes as soon as China’s ports reopened.

The spread of the pandemic across the world, however, has changed that model. As governments in developed, importing countries take ever more draconian steps to reduce the spread of the disease, economic activity in vast swathes of industry is grinding to a halt.

With that comes uncertainty, unemployment and recession. Consumers unsure when their next meal is coming from do not need new iPads or Nikes. Inventory levels are already relatively high and with demand falling, there will be little need for importers to bring in anything new anytime soon.

But the real challenge for carriers is going to be financial. Despite indications that the first quarter of 2020 has been less traumatic than might have been expected, the slow burn from coronavirus will drag on for many months.

Lines that are reliant on cashflow will see that cashflow disappear as soon as the latest shipments, ordered before the slump in demand took hold, make their way through the terminals. After that, the taps could well turn off.

Carriers have successfully managed capacity to hold up rates to date, but that hegemony could fall fast as cash grows thin. Putting ships into layup works for a while, but those ships still cost money to run even doing nothing.

It is still early days in this crisis, but some cracks are already beginning to show. Pacific International Lines, already facing difficulties before the coronavirus outbreak, is again struggling to pay its bills.

Whether this is the shape of things to come remains to be seen, but these are not good times for container shipping.

While China is seemingly getting back on its feet, the rest of the world is facing a severe economic slowdown with widespread lockdowns in place.

Activity is slowly returning to the Pacific markets, but the Atlantic basin faces headwinds for dry bulk trades.

Owners and operators told Lloyd’s List that they were coping with the situation with several measures in place to minimise disruptions.

Capesize earnings have been the hardest hit because of lower iron ore from Brazil and Australia amid weather-related disruptions in both regions. At the same time, industrial activity dropped in China following lockdowns in key steel-producing areas.

Although market participants are revising forecasts to the downside for this year, many are still holding out for a recovery in the second half of the year, but that is dependent on some sort of containment to the virus pandemic.

Vital grains trades appeared to be the only supportive factor in the market, keeping smaller sizes afloat, but supply chain issues may dim prospects even there.

There are reports of port restrictions and quarantine efforts to contain the spread of the virus. Uncertainty prevails.

Already, there has been conflicting reports at South American ports with stevedores at Santos in Brazil calling for time-out to reduce the risk of infection. Those pleas were however overturned and normal operations were reported by Santos Port Authority in statements during the past week.

The grain workers union in Argentina announced activities had ceased as of March 20, although three days later, the Timbues port was said to have resumed operations, according to Reuters. But, truck drivers were finding it hard to get to the ports, meaning grains exports were at risk during what was slated to be a strong season.

Brazilian mining giant Vale was meanwhile mulling the idea of closing its distribution centre in Malaysia. It finally decided to close the terminal until the end of March.

It also warned that several of its mining operations could be affected by the virus.

Queensland ports, barring Brisbane, which lifted some restrictions earlier this week, have imposed restrictions for vessels emanating from high-risk areas.

All is not lost though as congestion in ports is seen as a positive for freight rates as vessels are tied up for longer.

There are about 13% of panamaxes idled for more than 14 days, according to Klaveness, the highest level since 2017, while 9% of capesizes are idle, less than the amount idled after the Brumadinho dam collapse in January 2019.

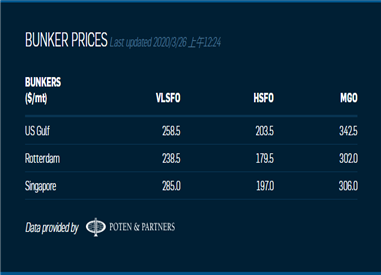

Today's Bunker Prices: